29 Nov How we react and should react to change

There is nothing new about fast-paced changes in our business and personal lives. However, the fact that our professional success as well as our personal well-being depends on our reaction to these changes is enough of a reason to talk a bit about these reactions and what we could do to be better equipped for the changes we face on regular bases.

How about a small two-stage experiment before continuing reading this article? Don’t worry, it probably won’t hurt.

Interlock the fingers of your hands – as seen in the picture above. Now unlock the fingers and simply change them in a way that the other thumb is on top. Feels weird, doesn’t it?! Let’s head on to the second stage and cross your arms in front of your chest. Now re-arrange your arms and have the other one in front. If you are like many other people (me included!), you struggled hard – especially in stage two.

What does this experiment tell you about yourself and your attitude towards change? What does it tell you about your attitude towards the unknown or the uncommon? What did your body tell you with regard to doing something for the first time or out of the ordinary?

This article explains what is happening in your head while you are doing something new and which factors you need to actively address to not struggle with change but engage in it with medium to little effort.

In times of rapid change, we instinctively try to hold onto patterns we are familiar with

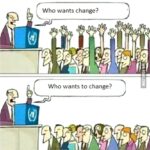

Change happens everywhere and change happens fast. Sometimes it seems as if nothing is certain and that everything eventually is bound to change. Although change occurs naturally, we very often perceive it as something that goes against our “modus operandi”. Since many of us most of the time are uncomfortable with the unfamiliar, we naturally search for shapes and styles of things we know and hold for true in everything new that comes our way, regardless of the sometimes obvious deviations from the “norms” we assigned to these things. As our surroundings evolve from one state to the next, our cognitive patterns we rely on should transform itself accordingly. However, unlike our attitude towards external change, which is not necessarily purely negative (after all, many recent changes, especially in technology and transportation, have given us access to conveniences, information and places previous generations didn’t even dare to think about), the sheer thought about changing ourselves, our beliefs and the things we hold dear, frightens us or at least makes us feel uncomfortable. Just like our small-scale change experiment from two minutes ago, this popular comic strip demonstrates our perspective on change pretty well.

We therefore see problems arise when we maintain these parts of our collection of patterns that keep us from accepting and going with natural change. They inhibit us from changing ourselves, as we are inclined to rely upon old (thinking) habits. The fact that we cannot effectively adapt to an ever-changing world takes its toll on us: our organizations flounder as they try to keep up with more agile competitors who better react to these changes than we can; cognitively we struggle to make sense of a new environment almost every day; and our health suffers equally, since we constantly are in danger of being overwhelmed by fast-paced phases of transition.

The mental pattern library that we thought serves us so well, presents itself as a source for potential danger and harm to us and our organizations.

In times of rapid change, we often need to resist our primal instincts and embrace small revolutions

The universal definitions of change almost always include that we go from a known to an unknown state. Our reactions to change are therefore dependent on the way we perceive the unknown state. But since this perception in turn is linked to our expectations and comparisons to past events (formed patterns) we have difficulties in taking new situations at face value. The consequence is obvious and straightforward. When our reliance on patterns from the past is detrimental to our reactions to present and future changes, we need to cut our dependence on these patterns. We are facing unique events and situations on a regular – almost daily – basis. The notion alone to form a cognitive inventory of structures that we can use to predict or even react to the future seems ludicrous. We know about constant changes everywhere and instead of comparing them to past situations, we embrace their revolutionary character as good as we can. Browsing through previously formed patterns and probing their applicability to completely different scenarios is time-consuming and, for all we know, the next change keeps rolling towards us and will shake the foundations of our cognitive library. After all, there is not much else we can do. Or is there?!

Solving the change paradox

Let’s hold on for a moment to summarize. Patterns and structures are bad because they keep us from accepting and going with natural change. Should we therefore tear and burn down our mental pattern libraries – a feat that is far from being easily realizable – and take every change as it comes without relying on our previously obtained knowledge? Not so fast. The same mental library we equipped with patterns and structures throughout our lives is also our biggest asset in effectively reacting to change. In fact, the bigger its inventory, the more successful we can handle change in our lives. The success of solving problems, making decisions and coming to conclusions depends foremost on our ability to apply the vast set of patterns we stored in the past to situations we face in the present. As in many contradictions and paradoxes, here as well, the truth is in the middle. The success in using patterns from the past reaches its climax when we apply them with caution to positions in the present. Each new situation and each new scenario brings its own characteristics we need to keep in mind while browsing through our stock of structures. We rarely find circumstances that are identical to the ones we already experienced. But if we focus on their main features and recognize what makes them special, we are better able to find and combine the right patterns in our cognitive database and make informed decisions about how to effectively react to changes.

Let’s assess and discuss your reactions to change. What are your first reactions to an unfamiliar situation? How comfortable are you in both collecting and applying patterns? How easily can you build cognitive bridges between past experiences and current events?

Get in touch with us if you want to speak and learn about effective reactions to change. Simply send me an email at philipp.kitterer@iak.de.

We are excited to hear from you and looking forward to exchanging thoughts with you.

In the meantime you might find the following articles of particular interest to you:

4 Reasons why you fail at change

Leaders who get change right know how to listen